French photographers Carrets return to Slovakia to settlements: We will only take out the camera when we are welcomed

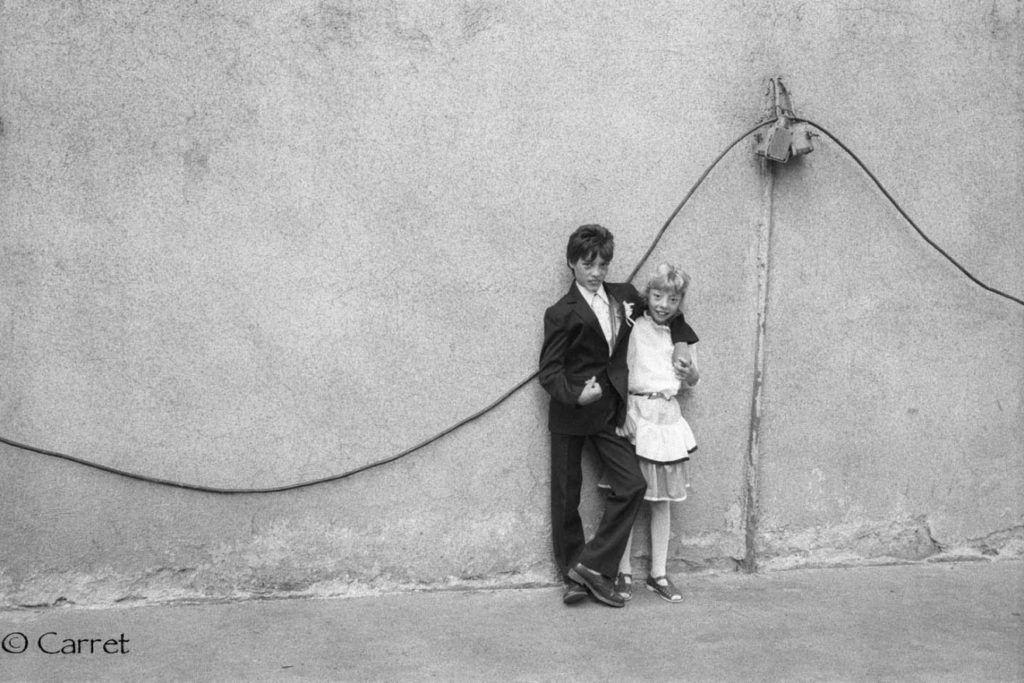

„Modernity has also entered the life of the Roma,“ say French photographers Claude and Marie-José Carret.

Slovenskú verziu textu nájdete tu, rómsku tu.

For almost 40 years, the French couple Claude and Marie-José Carret have photographically documented the life of Roma in Eastern Europe. They also repeatedly return to Slovakia. They go mainly to Klenovec – a village in Malohont, where about 250 people live, excluded from the majority.

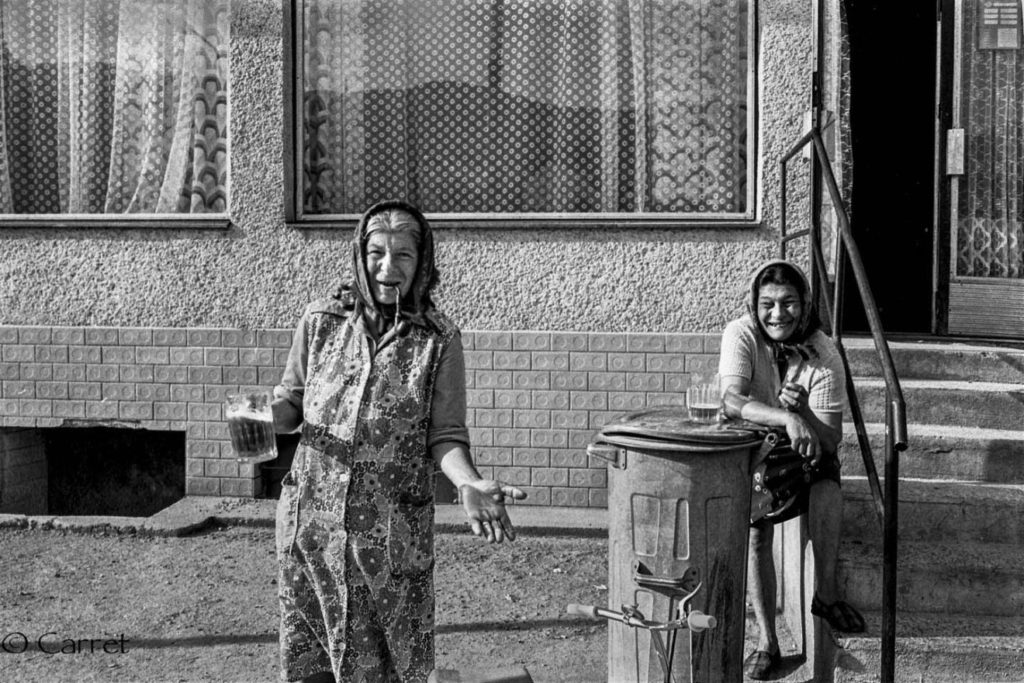

„Residents were surprised that someone might be interested in them,“ the Carrets describe their first visits. „We carried away the knowledge that although their way of life is different from ours, it is full of joy, despite the difficult living conditions. Their human warmth can be felt.“

In November, they came to Slovakia to launch their photographic book Otisk cest, which presents the traditions, crafts, and festive and mundane moments of Roma families.

In an interview hosted by the French Institute in Slovakia, they explain, among other things, how they got from Western Europe to Roma culture, what attracts them to it, and how they see the differences between Romanian, Hungarian and Slovak Roma.

The questions were mostly answered by Claude Carret. His wife, Marie-José, adds that they do so for the sake of simplicity. Whether in front of a dictaphone or behind a lens, she says, this is a shared „four-eyed photographic journey.“

You met Slovak Roma for the first time in 1984 in Klenovec. Then you returned to Slovakia for ten more years, and you still come here. What happened at the first meeting that attracted you to the Roma community for so many years?

We first arrived in Slovakia during the Czechoslovak era. We came to Klenovec as part of the cultural partnership between the French city of Rennes and the Czech city of Brno. In Klenovec was a cultural officer at the Slovak Embassy in Paris, who already knew a little about my work.

I started photographing in the 70s and Marie-José in the 80s of the last century, we were already involved in Roma culture. So, knowing about my work, he directly invited us to visit his native village.

For us, it was a completely unknown village in the south of Slovakia. In the beginning, we were traditionally officially welcomed and then suddenly found ourselves alone and had the whole weekend ahead of us. There we met Helena Olga Hrušková, who spoke German, so they put her in charge of us.

That Sunday was a Roma holiday, and there were only Roma in the village, the „gadjas“ could not be seen. We came out of curiosity to celebrate their holiday and then continued to one of the houses where we started taking pictures. However, we were not in Klenovec at that time specifically because of the Roma, our intention was rather general. We wanted to take pictures of traditions and landscapes – so why not Roma too?

Having established contact with Mrs Hrušková, three months later we returned and kept returning for ten years. She became a kind of adoptive mother to us, and something very strong was created between us. So, two or three times a year, we came to Klenovec and we always brought our previous photos. And gradually we began to understand the local circumstances.

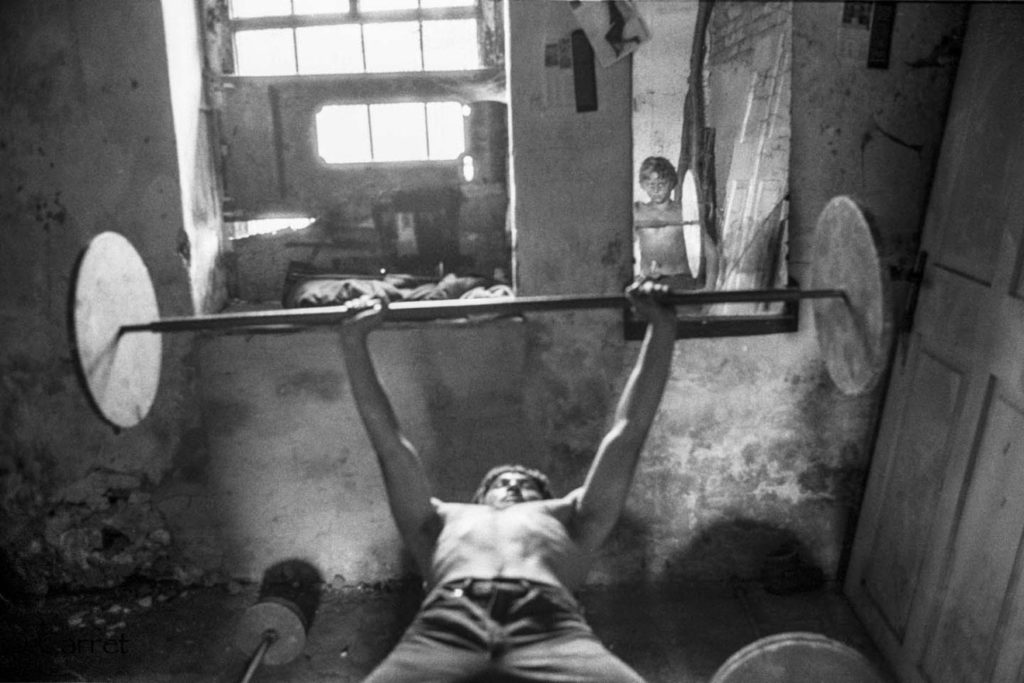

The Roma we photographed mainly musicians who had the privilege of living in the middle of the village, where they accompanied folklore ensembles.

What attracts you to Roma culture that you pay such meticulous documentary attention to it?

Our photographic approach is the photography of the moment. This means that we only start taking pictures when we feel that the moment is right and that we have integrated into the environment. After meeting Roma musicians, we realized that there were settlements that we had no idea about.

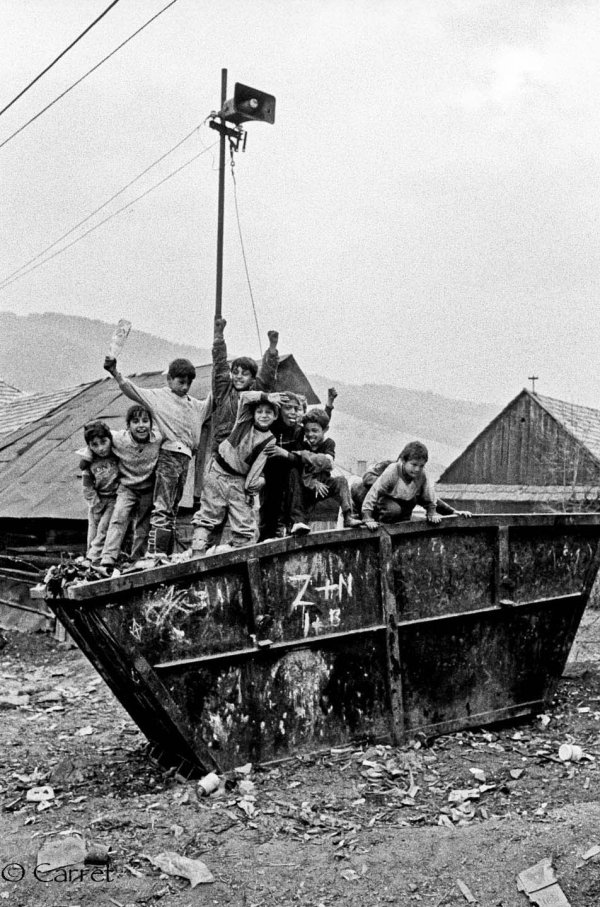

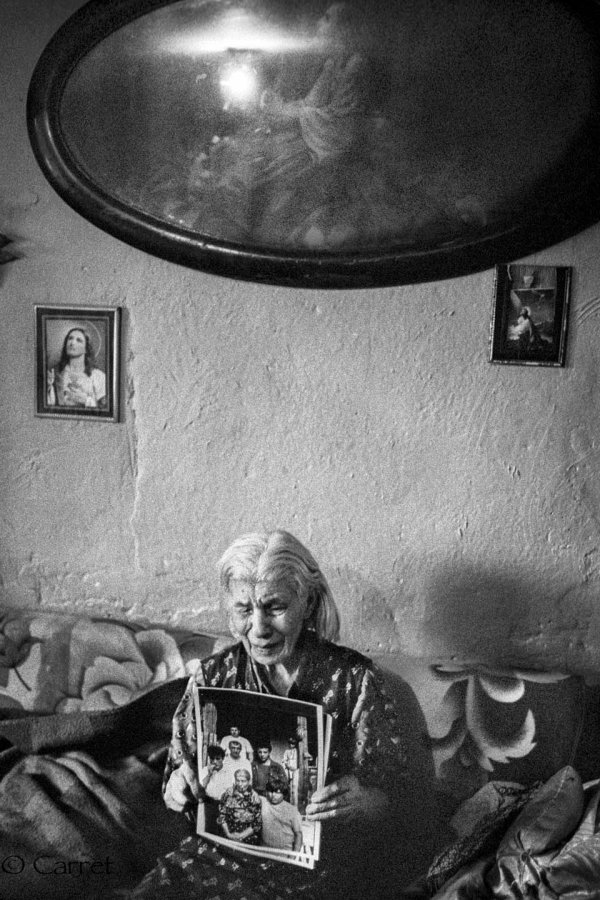

We started going there and the residents were surprised that someone might be interested in them. We were very well welcomed. We carried away the knowledge that although their way of life is different from ours, it is full of joy, despite the difficult living conditions. Their human warmth is felt. There are families among them with whom we have become close and remain close to this day. Our photographic concept is about duration, we are not interested in just one moment.

However, before we became interested in the Roma, we also addressed other communities. For example, for eighteen years we have been working with refugees in France from Laos or Cambodia. We have always been interested in other cultures and the differences between them out of curiosity.

Your photographs offer an intimate view of the world of Roma. How did it happen that you earned their trust and were able to document their lives so closely?

It is both because of the duration of our interest and because we have always brought back our photos to show. However, not the ones that we wanted to keep, but the ones that interested them. It took a while, but after a few years, we developed these bonds.

As soon as we entered the village, our photos began to circulate in the settlement and we heard: „That’s my uncle, that’s my aunt!“ There were, of course, moments of complexity in the language when we did not fully understand each other because we do not speak Roma.

However, I think they felt really honoured that we were interested in their culture. We realized this recently when we returned to Klenovec with a filmmaker who was making a film about us (laughter). When they saw him, they hugged us because they felt they were finally important. At their level, it was something really powerful.

You return to the settlements repeatedly. How have they changed in the four decades you’ve been visiting them?

They are already developing. We can see that the settlement near Klenovec is emptying because many people have moved into the village, where there is therefore a more diverse population. Schooling, in turn, has caused children to develop more, some of them are already excellent. It is going slowly, but it is evolving and the changes are visible. We can see the development for the better, also we have been going to Kežmarok and Veľká Lomnica for years.

For example, when we now go to the village of Rakúsy near Kežmarok, we see that the children from the Kesaj Tchave art ensemble (an ensemble that works only with children from the settlements) no longer continue dancing because they have a job. The fact that you have a job inevitably improves living conditions. Likewise, the fact that people are integrated results in their moving forward.

How has your perspective and view of the Roma changed over the years?

It has not changed, because we have always respected them and treated them as well as other citizens. We are pleased that Roma integration is progressing, racism is receding somewhat, and we are slowly moving away from clichés and stereotypes.

However, our view of them has not changed, because we have always considered them to be the same people as we are, and we had no problem with each other. We have never had any prejudice against Roma culture.

Do you have one among your photographs of Slovak Roma that has stuck in your memory over the years?

Ten yes, but one no. We love all our photos. (laughter) After all, we’ve taken a lot of photos during those 37 years, so it’s hard to choose one. For example, we like all the photos from the book Otisk cest, which we presented in Bratislava.

In a way, we are proud to have a smaller cultural heritage. Klenovec is a community of musicians and we have made a kind of memoir about them without being aware of it.

The ethnomusicologist Petr Nuska, with whom we collaborated, also does a great job around the musicians from Klenovec.

Our work is a cultural heritage because all this will soon disappear. After all, modernity has also entered the life of the Roma. We are currently in contact with the Museum of Roma Culture in Brno, to which we want to leave our archives.

You photographically record the life of Roma in Slovakia, Romania, Hungary and Ukraine. Do you see differences between the Roma and their culture in these countries?

Yes. For example, during communism, Roma in Slovakia were forbidden to migrate. Therefore, through the generations, they no longer remember which subethnicity they belonged to. There was the same law on the prohibition of migration in Romania, but the Roma there nevertheless continued.

Therefore, we still find various sub-ethnics there – there are musicians (lovaries), horse breeders (lotharis), metalworkers and so-called calderashi, that is, cauldrons. This makes them photographically very interesting.

Roma is not a homogeneous ethnicity. They came from different parts of India, so we cannot expect the same Roma everywhere. We also see differences in women’s clothing and clothing in general. In Romania we see more traditional clothing, in Slovakia not much anymore – here every one is already dressed like us.

And it seems to us that in Romania, the Roma have preserved the Roma language more. In Slovakia, it is hardly spoken anymore. I can think of a detail. In Transylvania, for example, there are Roma of Hungarian origin who are goldsmiths, but first of all, they are people who shape the gutters. You can see them walking with a piece of eave under their arm. They have an amazing atypical moustaches and go to the barber every morning.

I believe that the Roma have a great capacity to adapt. For example, the Kalderaš Roma became truck drivers overnight. They were always able to adapt and find new jobs.

Are you also in contact with Roma from Ukraine? Many of them were already among the most vulnerable groups before the Russian invasion. How did the war affect their lives?

The last photographic work we did was in Ukraine. We did not find many Roma in the regions we went to. However, we still have one or two photos in the book.

The situation was already difficult for the Roma before the war, and at the moment, with a few exceptions, we have hardly any reports of them. And the news we do have from these exceptions is quite negative.

Many Roma families live in difficult circumstances. How do you balance taking pictures of people from poor backgrounds and preserving their dignity?

We have always tried to avoid voyeurism. Sometimes the contrast between those situations is the relational aspect. It can cause these people to be able to laugh in addition to the difficulties of everyday life, although their material situation is complex.

Our photographic approach is the opposite of what reporters do, who come to the site for a couple of hours and wait for their clichéd photo. Although we show living conditions, we are not looking for a shocking photo.

This is for journalists who have four to five hours to take such a photo in one place. This is the difference between taking a photo over a long period and taking a photo for the press or the Internet. We don’t have an angelic approach to photography either, but we try to be as realistic as possible.

What interests the French in the photos of Roma culture?

They are interested in differences. We have travellers who have very comfortable living conditions, so I think it’s about their curiosity and also their relationship with music.

Roma culture with some of its aspects invites dreaming and that is where the interest in it flows. Roma culture is primarily oral – singing, stories or fairy tales in which there is not much history.

It´s a current calling for dreaming through films directed by Emir Kusturica and Tony Gatlif. And the French a little bit through our photographic work.

You came to Slovakia to inaugurate your new book. What does it capture?

It is a book that is also a surprise to us because we had no control over anything when it was created. We just provided photos and then discovered it.

It is a book where there are practically only our photographs and the introductory text of the Museum of Roma Culture in Brno, which is its partner. There are no unnecessary speeches or expressions of attitude towards Roma culture.

It is a book of photographs of Claude and Marie-José Carret, our friend Vladimír Židlický wanted it this way. He arranged for its release and found funds for it. We have been friends for 37 years, dating back to the days of the cultural partnership.

We were connected by photography, so during those decades of documenting Roma, we repeatedly stopped in Brno to visit his family.

We helped Vladimir with the presentation of his work in France, and he wanted to confirm our friendship with a surprise in the form of this book.

Claude and Marie-José Carret areFrench photographers, specializing in landscape and reportage photography. Claude started photography in 1976, working as a cultural advisor in a gallery in Chartres de Bretagne from 1998 to 2002. Marie-José hails from Trier, Germany. She began photographing in 1980. Since 1984, the couple has repeatedly travelled to eastern European countries, documenting the lives of people from excluded communities. They visited Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Romania, Moldova and Ukraine, among others. They published their first book in 1996 together with their friend the Roma writer Maté Maximoff. They exhibit their photographic works in France and abroad.

Našli ste v článku chybu? Napíšte nám na [email protected]